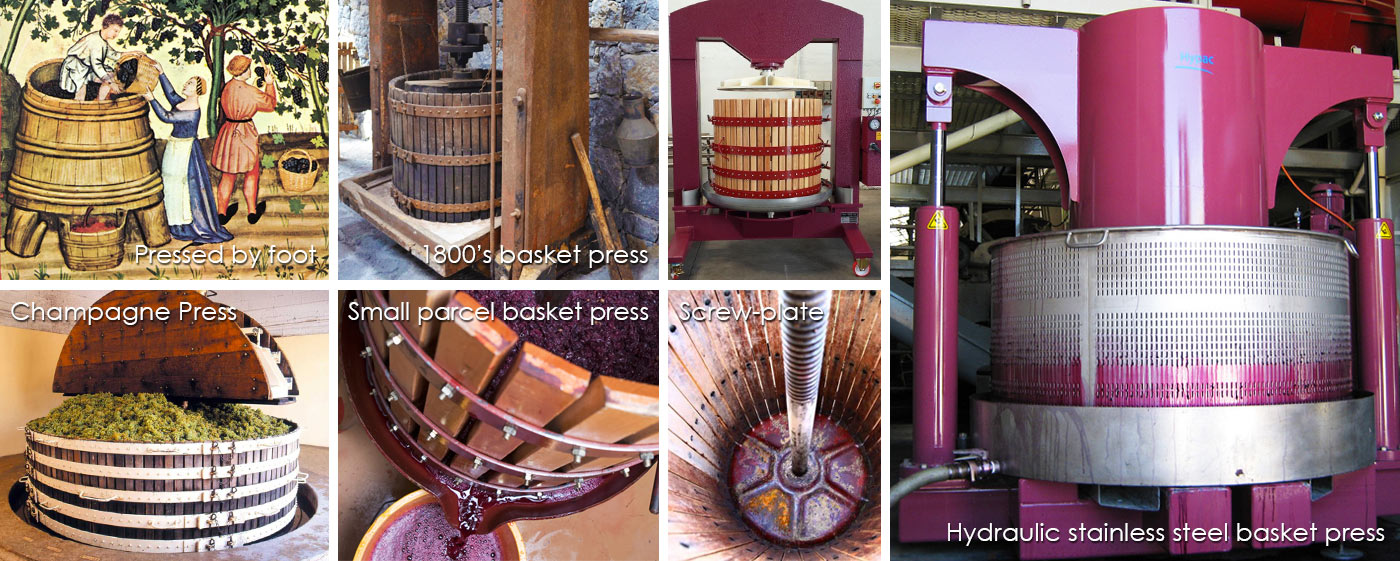

The Basket Press:

A 'Basket Press' (or wine press) is a unique device used to extract-squeeze juice from grapes before the winemaking process can start. There are a number of different styles and sizes of grape presses used by winemakers, but their overall function is the same. Each style of press exerts controlled pressure in order to squeeze the desired amount of juice from the grapes.

The pressure must be controlled, especially with grapes, to avoid crushing the seeds and releasing undesirable acids and tannins into the juice. Wine has been made at least as long ago as 6000 BC; recently a wine press was unearthed in Armenia with red wine dated 6000 years old. A basket press consists of a large basket and a top-plate that can be tightened, pressed down - which is filled with the harvested wine grapes.

Once the initial 'free run' juice has been gathered (which a number of winemaker use for special wines, plus is very important in Champagne), pressure is applied to the grape skins. This juice is very concentrated and has more tannins and with red wine has more pigments than the 'free run' juice.

Pressure is applied through a plate that is forced down onto the berries. The mechanism to lower the plate is often either a hand-screw or a hydraulic device. The juice flows through openings, gaps in the basket. The basket style press was the first type of mechanized press to be developed, and its basic design has not changed in nearly 1000 years.

After pressing is complete, the remaining skins and debris called pomace, is often used to fertilize the vineyards, thus renewing the cycle of the vine to the bottle. The free run and pressed juice components are kept separate during the subsequent fermentation and racking processes. At the winemaker's discretion, they may eventually be blended to make a wine with certain characteristics. Basket presses produce very high quality juice, but are labour intensive and expensive to use. They are ideal for small amounts of high quality wine.

When deciding on the size of basket press, remember it needs to be at least a quarter full in order to function efficiently. After the first pressing has finished, it is necessary to empty out the pressed pomace, mash, crumble it and then press again; the extra volume of juice obtained from the second pressing is approximately 10-15% of that from the first pressing.

Fermentation:

Fermentation - *(the art & science of turning fruit juice into wine) - is basically the conversion of grape sugars into nearly equal parts of alcohol and CO2 by the action of yeast.

When the harvested fruit reaches the winery - the grapes can either go into a de-stemmer / crusher which separates the larger stems from the crushed fruit pulp, and then feeds them into a rotator which in turn removes the seeds, which can impart bitter qualities to the wine. But some winemaking techniques / wine styles will for a period of time may keep all or part of the grape bunches’ whole (leaving the berries on their stems)

When making white wines - the grapes have the juice removed from the skins at this point (i.e. the clear juice is promptly pressed off, squeezed out of the grapes, with no skin contact). Whereas when making red wines - the red grapes are split / macerated and the juice (which is also clear) is fermented on, in contact with the skins to extract colour, tannins and more. Both of these processes liberate the sugars in the grape juice, ready for fermentation.

Most often a winemaker will introduce a cultured yeast strain into the juice. A cultured yeast may be selected for its ability to ferment alcohol to high levels, to ferment slowly, to make clean wines or to make highly aromatic wines. Cultured yeasts are a safe, predictable option as fermentation patterns and results are well understood.

An alternative to a 'cultured' yeast is to use ‘wild’ or ‘natural’ yeasts *(which all yeast starts out as originally). But wild yeasts are specific / indigenous strains that are present on grape skins, in a vineyard and in the winery. They are capable of producing wines with a bespoke range of flavours and characteristics. But can carry an increased risk of problems occurring due to their unstable nature, so a winemaker will typically pay more attention to the unpredictability of wild yeast. Many winemakers can and will use a combination of both.

A small amount of sulphur dioxide is also added at this stage. It is a natural way of precluding discolouration, oxidation, killing unwanted bacteria and encouraging a rapid and clean fermentation. *Note: All wines have a level of sulphur dioxide - as sulphur is a natural by-product of the fermentation process.

Fermentation usually lasts between 4 to 10 days for red wines, whereas white wines may require several weeks *(and occasionally longer). Whites are generally fermented at cooler temperatures (12°C - 20°C) to extend the fermentation and enhance the intensity of the fruit flavours. White wines can also be fermented in oak barrels (new and used) to balance additional flavour and add to the wine’s complexity, mouth feel and length.

Red wines require warmer temperatures (ranging from 20°C - 32°C) to extract colour, tannins and to integrate flavours. During the fermentation of red wines, the skins and pulp will float to the top of the vat forming a thick layer known as the ‘cap’ on the fermenting wine. This cap must be constantly submerged back into the wine to extract colour, tannins and flavours. This is often referred to in a wine tasting note as - ‘pumping over’ or ‘plunging’ the cap.

Carbon Dioxide is a by-product of fermentation and is released in substantial amounts during fermentation. The fermenting container must have a way for the carbon dioxide produced by the yeast to escape in a controlled, safe manor. As CO2 can be lethal to winery staff as it displaces oxygen and is an unseen killer. As CO2 is heavier than air, it sits at the bottom of tanks and other confined spaces in wineries and has been responsible for numerous winery deaths.

Fermentation must be monitored - as long as the liquid is still bubbling then the yeast is still active. A winemaker will regularly test the sugar content, colour, acidity and alcohol levels during fermentation. The process may be stopped before all the sugars have fermented out completely (fermented dry) to retain some residual sugar or sweetness. For instance this happens with Port wine when fermentation is arrested-stopped, when a clear brandy spirit (a neutral alcohol) is added, to retain sugar and achieve a required level of alcohol.

Most red wines and a number of white wines can also undergo malolactic fermentation after this point. This is usually deliberately initiated by the winemaker. Technically a bacteria (from the lactic acid bacteria family) is introduced - which turns the harsh ‘malic’ acid to softer ‘lactic’ acid. In practice, it is more noticeable in white wines as producing a smooth buttery texture and accompanying creamy aromas. It is employed in almost all red wines, particularly those made in cooler climates, where the wine would otherwise be too high in acidity. Sometimes only a portion of the wine will be put through malolactic fermentation; the winemaker will select a certain number of barrels or drain off a portion of a tank and set the process in motion.

After fermentation, the solids are removed from the wine. Most solids suspended in the wine will settle out on their own with time. However, this could take months and does not always result in a perfectly clear wine. So wineries can/will use fining agents such as bentonite *(vegan friendly), which is a type of clay, or egg whites to remove these suspended solids. Filtration is also used to remove the dead yeast, protein and bacteria cells - which also stabilises the wine. Clarification is usually undertaken via filtration, centrifuge, racking or fining. After the wine has been clarified, fined and stabilised it is then ready for bottling. However, a couple of further stages (like further ageing in barrels or bottle) may take place before.

Barrel Fermentation:

Barrel Fermentation is the process of fermenting wine in oak barrels instead of large concrete vats, eggs or stainless steel tanks. Fermentation = 'the natural process that turns grape juice into wine', fermentation is actually a chain reaction of chemical reactions. During this process, technically called - primary fermentation, the natural sugars in the grape juice are converted by the enzymes in yeasts into alcohol.

Barrel fermentation requires very careful cellar attention. The barrels are usually made of oak and are about 225 litres in size, although larger sizes are used occasionally. Even though barrel fermentation is more expensive (due to the added cost of the wine barrel in making the wine) - and less controllable than fermentation in temperature controlled stainless steel tanks.

It is agreed by those in the know, that it can imbue certain wines with complexity, rich, creamy flavours, layers of integrated oak characteristics, better aging capabilities, along with more engaging palate structure, texture, mouth-feel and a longer finish.

Barrel fermentation is especially beneficial to white wines. First, since white wines lack the tannins of red varietals, the wine can instead draw tannins from the oak barrels. White wines that have been barrel fermented have a less dramatic oak character / taste - than those wines that have been fermented in another stainless steel tank and then oak aged. The wine flavours are better integrated and harmonized. The fermentation process, tempers the flavours of the wood, imparting balanced flavours of oak. So in the wine, you will find hints of cinnamon, vanilla and cloves rather than over whelming harder oak flavours.

In particular, a quality white wine can become more creamy, rounded, buttery and toasty on the palate after being barrel fermented. Barrel fermentation is usually associated with white wine grapes like Chardonnay, but also on occasion with Sauvignon Blanc (e.g. Fumé Blanc & Pouilly-Fumé style wines) and occasionally Chenin Blanc, Grüner Veltliner and Viognier can be processed in this way.

Plunging the Cap:

The 'cap' in winemaking - is the layer of grape skins, pips and other solid matter that rises to the surface of the wine during the vinification process.

When making several different styles of red wine, grapes are put through a crusher and then transferred into open fermentation tanks (made of wood, concrete or stainless steel). Once fermentation begins, the grape skins are lifted, raised to the surface by the carbon dioxide C02 gases which are released during the fermentation process.

So this layer of grape skins and other suspended solids is known as the cap. As the skins are the source of colour, flavour, aromas and the tannins - the cap needs to be macerated (mixed in) through the liquid several times each day, or punched / plunged down.

This is traditionally done by plunging through the cap, known as 'Pigeage' - a French winemaking term for the traditional plunging of grapes in open-top fermentation tanks. The cap of grape skins and pulp floating on top of the juice in red-wine fermentation inhibits flavour and colour extraction, may rise to an undesirably high temperature, and may acetify (turn to vinegar) if allowed to become dry. Such problems are avoided by submerging the floating cap several times a day during fermentation, to drown aerobic bacteria and encourage cuvaison (contact). This operation is comparatively easy with small fermenters, becomes much more difficult with large fermentation tanks.

A technique to extract these key red wine components is done by periodically pumping juice from the bottom of the tank over the cap. However, fine wine producers, to enhance the extraction of colour, flavours and tannin from the skins, often prefer to punch/ plunge down the cap in order to submerge it into the wine, or even to drain the wine from the tank and then splash it back over the cap to encourage greater circulation of the cap throughout the wine (a technique known as 'rack and return').

Whatever method is chosen, winemakers often extend the maceration period beyond the end of fermentation to encourage the full extraction of colour, aroma, flavours and tannin. Once this process is complete, the wine is pressed off the skins and transferred to oak barrels or stainless steel tanks, to commence the next stage in the winemaking, the aging process.

Pumping Over:

The French wine term or phrase: 'remontage' - (pumping over) is the drawing off of the grape juice or 'must' from the bottom of a tank or open fermenters and pumping it over the cap (composed of grape skins that forms on the top). Used to extract colour, aromas, create even temperature distribution, more flavour and tannins when making red wine, plus ensure optimal extraction and so the cap doesn't dry out and develop unwanted bacterial spoilage.

Not all pump-over's are equal. There are many ways to pump over. Ask a number of winemakers how to handle a pump-over and be prepared to hear an array of answers. With pump-over's, you have to decide on: how often, how many per day, how long, how warm, how many litres, how fast, how gentle - for each parcel and tank.

And then adjust it to each stage of fermentation and to how the flavours and tannins are progressing. It is also important to try and remember how you did it last year and how it tasted yesterday - and last year. Simply put, there are lots of reasons and ways to tweak with the pump over at each stage of fermentation.

Generally, pump-over's are more gentle and shorter when the grapes first go into the tank. At the start of fermentation it is effective, it is less so when done towards the end of fermentation. It is at this stage where the colour is slowly coming out of the skins and there is very little heat or alcohol to help with extraction.

Once the fermentation begins, the pump-over's become more frequent and longer in an attempt to pull out, extract the best of the flavours by moving larger volumes of juice through the warm skins but the warmer it is, the faster the fermentation progresses and the less time it leaves to get all that the grape skins have to offer. It can be common practice to pump-over a third to a half of the tank volume each time.

Whether it is once or five times a day, this is the time that we are hooking up to each tank, climbing on top, checking the cap, recording its Brix level, measuring temperature, tasting its progress and enjoying the most obvious sounds and smells of crafting red wine.

Stainless Steel Wine Tanks:

The process of wine production has remained much the same throughout the ages, but new sophisticated machinery and technology have helped streamline and increase the output of wine. Whether such advances have enhanced the quality of wine is, however a subject of debate for some. These advances include a variety of; mechanical harvesters, grape crushers and temperature-controlled stainless steel tanks to name a few.

The procedures involved in creating wine are often times dictated by the grape and the amount and style of wine being produced. Certain types of wine require the winemaker to monitor and regulate the amount of yeast, the fermentation process, temperature and other steps in the winemaking process.

A universal factor in the production of quality wine is timing and the control from each step to the next, stainless steel tanks are one of the tools a winemaking uses to have more control. Red wines are generally fermented in large open-topped stainless steel tanks, neutral wood vats or sometimes concrete vats that don't add flavour to the wines.

In order to extract colour, aroma, flavour and tannins from the red grape skins, the 'cap' (the skins that float up and bind together on the surface of the must) needs to be broken up and submerged (plunged down) at least three times a day. This process can be done manually, but today it is more often being done by mechanically.

For white wines, the most common fermentation vessels are stainless steel tanks and oak barrels (though concrete tanks are still used and more recently concrete eggs). Stainless steel tanks retain fresh fruit flavours and prevent the wine from overheating during fermentation. As the winemaker can have precise control over the temperature inside - due to the cooling / ice jacket on the outside of the tanks. A cooling jacket is basically an extra exterior wall for the tank that allows cold water/glycol to be passed through the space between the jacket and the tank wall in order to change the temperature of the wine inside the tank. On small tanks this can be done with cooling plates or snakes, but for tanks over 1000 Litres in size the tank requires a jacket in order to have better control over the heating/cooling of the wine inside.

In the mid 1950's no more than 3 wineries in the world were using temperature controlled fermenting tanks. 1961 - Château Haut Brion installed Bordeaux's first stainless steel tanks for temperature controlled fermentation. Today this is a very familiar site the world over, for example nearly every Champagne House ferments their base wines in stainless steel tanks and store their 'reserve' wines in stainless steel tanks at precise cold temperatures for up to 15 years for blending their non-vintage Champagnes.

Tannins:

Tannins are a family of natural organic compounds that are found in wine grape skins, seeds/pips (which are particularly harsh) and in the stems. Additionally, during the aging process, new oak barrels infuse tannins into the wine. They are an excellent antioxidant and natural preservative; also helping give the wine structure and texture. Tannins also provide an important flavour profile in wine.

Winemakers have a good degree of control, using tannin to enhance the wine. They use specific juice extraction techniques to reduce or increase the amount excreted. Specifically - gently squeezing the grapes to extract the juice; winemakers take great care to minimise undesirable tannins from seeds by pressing grapes gently, to avoid crushing them. For example there are tannins in white wines, but typically the juice is removed quickly from the skins before fermentation. So the level of tannins are much lower than in red wine, though oak tannins can be found in white wines.

In the case of making red wine, grape skin contact is essential and for a longer period - the crushing of the grapes is more violent, and barrel aging is more common and again longer - resulting in a stronger tannin structure in the wine.

In concentrated quantities, the astringency from the tannins is what causes the dry and puckering feeling in the mouth, even described as 'furriness' around the mouth and on the teeth following the swallowing of red wine. This is sometimes accompanied by a bitter aftertaste, which is sometimes referred to as 'tannic'. Visually, tannins also form part of the natural sediment found at the bottom of the bottle as a wine ages.

A strongly tannic wine can be well-paired with richly flavoured cuisine, in particular game and red meats; the tannins help break down the fats, with a beneficial impact on both the wine and the perfectly cooked steak or dish.

A red wine that should age and improve for several years' even decades requires a high level of tannin. As the wine ages, the tannin softens and become less aggressive and noticeable. In many regions (such as in Bordeaux - France), tannic grapes such as Cabernet Sauvignon are blended with lower-tannin grapes such as Merlot and Malbec, diluting and integrating the tannin characters. Plus wines that are vinified to be enjoyed young typically have lower / softer tannin levels on the palate and finish.

Yeast:

The process of making wine (well in theory) is quite simple. A single cell organism of the genus 'Saccharomyces' consumes sugars (e.g. glucose) in wine grape juice and transforms it into approximately equal parts of alcohol and carbon dioxide.

It is the single-celled (unicellular) organism that we commonly call 'yeast' that are the real winemakers. The individuals who take the name 'winemaker' can largely be called technicians (yes harsh). Though a large percentage of the actual winemaking process has little to do with the winemaker.

A winemaker's main concern in the early stages of winemaking is to prevent spoilage of the juice, expressing a desired style and characteristics and then when ready - blending and bottling it. In other words, the yeast is doing a great deal of the work (converting sugars) and making the wine.

Wine yeast typically comes in 500 gram packets in dried form, which permits easy storage and start up. Each 500 gram packet is enough to start around 2000 litres of wine by direct addition. Packets may be stored at a cool room temperature or in the refrigerator (but once open they should be used promptly).

To develop a good understanding how wine is made, as opposed to preserved, you only need to understand the fermentation process. If there is an art to winemaking, and there certainly is, then it is the art and skill of controlling the chosen yeast for the grape varietal and style of finished wine required.

It is the art of selecting the appropriate yeast, introducing it at the correct moment, feeding and nurturing it so as to entice it into living, reproducing and dying in a set manner, and then cleaning up after it so as to preserve the natural fruit characters after its hard work. It is the art of controlling the temperature, the amount and kind of oxygen it is allowed to breathe, and feeding it the sugars and other nutrients it needs to serve the winemaker. For it is not in the nature of yeast to serve anyone, but rather yeast exists to serve yeast.

It could be said, that controlling yeast is the real art of making wine. It is very important to use high quality yeast in all your winemaking. Yeast is the workhorse that converts the initial sweet sugar must into great-tasting wine. It is also not surprising that the finest winemakers use quality dried wine yeast. If you are making quality wine, you want the best.

• Wild Yeast: Yeast is normally invisibly present on the outside of the grapes, stalks, stems and leaves in the vineyard and in the winery. Fermentation can be started with these indigenous wild yeasts: however, these may / can give unpredictable results depending on the exact types of yeast species present on the grapes, inside the winery and even oak barrels.

For this reason pure 'cultured yeast' is generally added to the juice/must, which rapidly comes to dominate and guide the fermentation. This represses the wild yeasts and ensures a reliable, controlled and predictable fermentation.

• 'Indigenous / Wild Yeast':

For inoculated fermentations', the size of the inoculum which yeast manufacturers recommend adding is large enough to ensure that the fermentation starts rapidly and is therefore dominated by this single strain. Many winemakers inoculate with a considerably smaller dose of yeast and they obtain some of the benefits of wild yeast fermentation. The result is a slower, longer fermentation, giving a base for native yeasts to have an influence on the fermentation.

Most of France and much of Europe practice inoculated fermentation. The exceptions are some of the small estates in Burgundy and the Rhône who use native / wild yeasts in most years. For these smaller Domaines, science and technology take a back seat to tradition, or 'doing it as their forefathers did'. While some New World winemakers have embraced many traditional European winemaking techniques, natural / wild yeast fermentation have caught on over the past two decades or so.

Wild yeast is not the secret answer to making great wine. Rather, it is a piece of the puzzle - one in a number of ways to add and develop complexity in wine. This quality factor coupled with the fact that the majority of winemakers feel these methods make their craft more interesting and challenging assures that the use of wild yeast will continue to grow in the production of interesting bespoke, character filled wines.

Blending Wine:

Blending wine can be as simple as taking two separate wines (i.e. Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot) and mixing them together - right through to complicating things and taking multiple varietals from multiple vineyards and even multiple regions and blending them to make a new wine with a unique style and flavour expression. It takes a lot of experience and a well trained palate to successfully blend wines for today's different wine markets - (e.g. countries expectations, retail and for restaurants).

A winemaker may blend wines for a variety of reasons: to adjust pH, acidity, residual sugar, alcohol levels, tannin or oak content or to improve the colour, aroma, flavour or length. As well as understanding all of the differences that exist from more than one vineyard, differences that develop from one fermentation tank to the next, different tannin levels between oak barrels, etc.

Wines, like Châteauneuf de Pape and Champagne, can be made from a blend of red and white grapes. Also Rosé Champagne is often given its' pink colour, from the addition of red wine (i.e. Pinot Noir wine) before secondary fermentation.

Other wines, like a Bordeaux are blends of the same grape colour. In the case of Bordeaux, the grape varietals; Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Cabernet-Franc and Petit Verdot are blended, in order to add the character of each grape to the final wine.

Even wines of a single grape varietal are (can be) blended, from different harvested parcels and or vineyards - plus from different tanks and barrels. In this case, wines that have been vinified separately (referred to as lots, batches, parcels etc...) are blended together. This blending may come about in order to create a specific style of wine unique to that vintage. At the highest quality level, individual vineyards are vinified separately, each adding their own unique character to the final blend.

Blending to make a Non-Vintage Champagne, the head winemaker (Chef de Cave) will taste all of the different parcels of Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier from the current vintage and their reserve (aged) wines. In order to figure out what to blend together to maintain/keep the house style (their unique Champagne style crafted year after year) consistent.

When blending a wine - you are trying to achieve a result where the final finished blend in the bottle, should be greater than the individual parts.

Vegan Friendly Wines:

Vegan friendly wines are increasingly talked about and a great deal more common place across all wine styles - though these wines often do not always include this information on the label. A number of people are unaware that wine, although made from grapes, may have been 'made' using animal-derived products. Because during the winemaking process, wine is often fined or filtered through substances called ‘fining agents’.

This process is used to remove: dead yeast, protein, cloudiness, off-flavours, off colouring, and other organic particles which are in suspension after the making of the wine. A fining agent is added to the top of the vat/tank or barrel, and as it sinks down, the particles adhere to the agent (which is positively charged), and are carried out of suspension. Note: None of the fining agent remains in the finished product sold in the bottle - and please note, not all wines are fined or filtered.

Winemakers are not required to put on their label which clarifier (fine agent) is used, since it is removed from the final product. Some winemakers also let the wine's sediments settle naturally, a time-consuming process. However, some winemakers will state on the wine label that their wine is unfiltered, because some wine connoisseurs prefer wine to be unfiltered.

Finding wine that has not been filtered with animal products can be difficult. The most accurate way to find out if a wine is acceptable for a ‘vegan-diet’ is to contact the winery and ask specifically what is used in the fining process for each wine.

• Examples of animal products used in fining are: gelatin, isinglass, chitosan, casein and egg albumen.

Of these fining agents - casein and albumen (derived from milk protein and egg white respectively) would be acceptable for vegetarians, but not for vegans.

As an alternative to animal products - Bentonite, a clay mineral, can be used to clarify the wine. There are several fining agents that are animal-friendly and used to make vegan approved wine. Carbon, bentonite clay, limestone, kaolin clay, plant casein, silica gel and vegetable plaques are alternatives.

Wineries clearly point out that once a wine has been fully fermented and bottled, only microscopic trace elements of these agents are left *(if at all) in the final wine, but to many vegans this is not a comfort. The good news is that wine labels are increasingly becoming more detailed and specific about the fining and filtering agents used. To put it in some perspective, if a person was to buy vegetables grown in soil outdoors, they would be exposed to more animal and insect residue than they would be in a bottle of wine.

But regardless of the fining agent used in your favourite wine - 'Always drink in moderation'.

Wine Diamonds:

Tartaric Acid (a.k.a Wine Diamonds) is the most common and distinctive wine acid - and is a particularly good preservative. A naturally occurring acid found in grapes and the most important acid in wine. A good level of acidity is essential for balance, the refreshing character of crisp whites, and the ageing potential in all wines.

Tartaric acid may be most immediately recognisable to wine drinkers as the source of 'wine diamonds', (harmless crystals) the small potassium bitartrate crystals that sometimes form spontaneously on the bottom of the cork, or fall to the bottom of the wine bottle.

These 'tartrates' are harmless, despite sometimes being mistaken for broken glass. They are prevented from forming in many wines through cold stabilization.

However, Tartaric acid plays an important role in the chemical balance of wine. By lowering the pH of fermenting 'must' to a level where many undesirable, bad bacteria cannot live, along with acting as a preservative after fermentation. With this the wine industry typically regards tartrate (wine diamonds) forming and dropping-out more as a sign of quality, than a problem or an issue to be concerned with.

Most commercial wineries cold stabilise their wines to avoid tartrate dropout. Cold stabilising is the process of lowering the temperature of the wine, after fermentation, close to freezing for approximately a week or so. This will cause the crystals to separate from the wine and stick to the sides of the stainless steel tank. When the wine is drained from the tank (e.g. a temperature controlled tank), the tartrates are left behind. Most quality and premium wines are cold stabilised in an attempt to minimize tartrate dropout.

So in summary - Tartaric Acid (wine diamonds) is a harmless occurrence, and if swallowed will cause no ill effect or harm, (possibly a slight gritty taste on the tongue) and 'wine diamonds' do not subtract or add any negative characters, aromas or flavours to a wine, as they are naturally occurring in grape juice, and are an important part of the winemaking process.