Cropping Levels / Yields:

In viticulture (grape growing) the yield is a measure of the amount of grapes or wine that is produced per unit area of vineyard and is therefore a measure of crop yield. There are 2 types of yield measures commonly used - the quantity of grapes per vineyard area and the volume (litres) of wine per vineyard area. Yield can often be viewed as an indicator for quality, as lower controlled yields are associated with wines with more concentrated, complex flavours, and the maximum allowed yield in many wine regions is strictly regulated for many wine styles / appellations around the world.

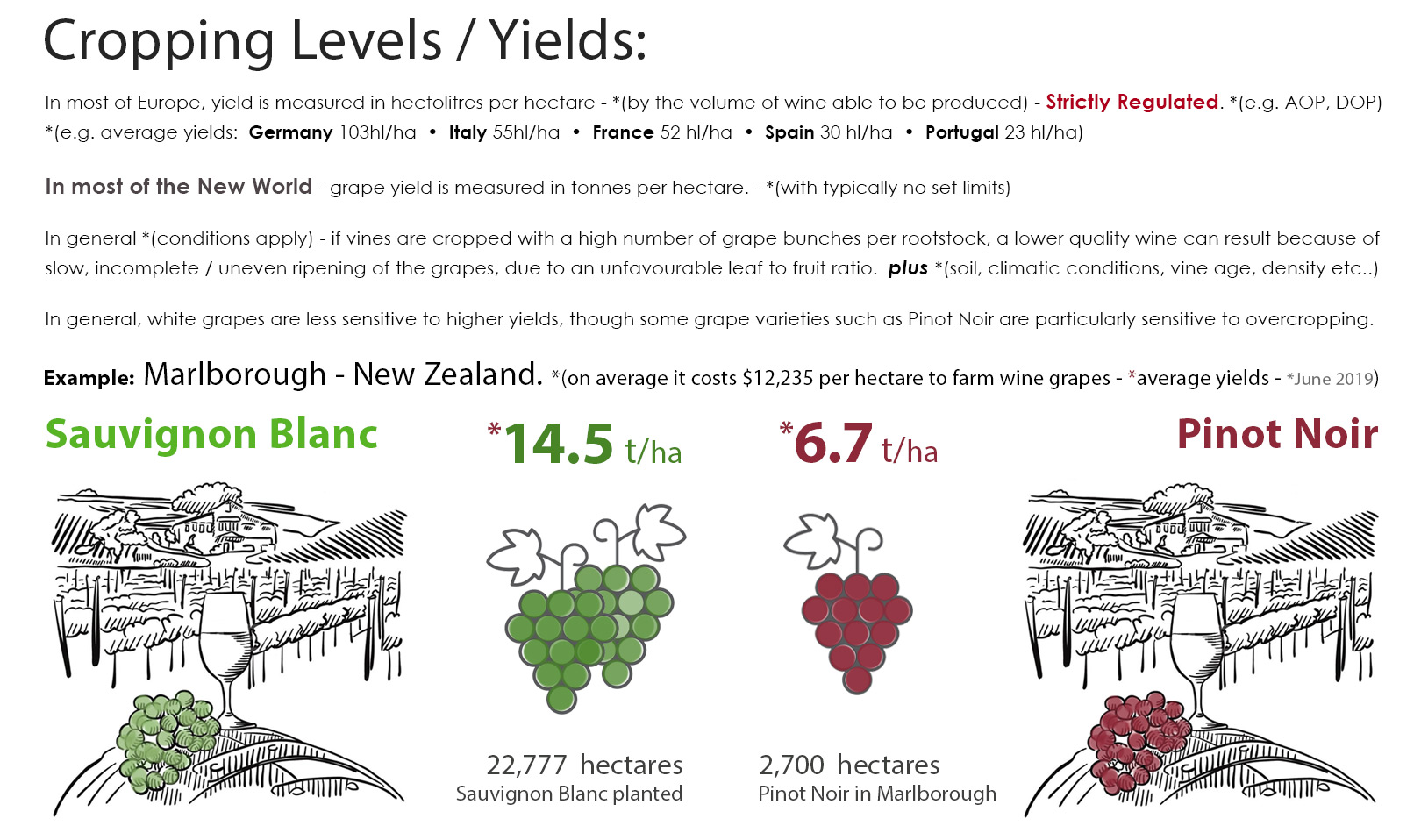

Across Europe, yield is measured in hectolitre per hectare - the litres of wine per area. In other winemaking counties around the world, yield is measured in tonnes per hectare - or by the mass/weight of the grapes, measured in tons or kilograms per hectare.

There are a great many variables that affect the yield of a vineyard - variety (white or red), vine age, row spacing and density, soil composition and vintage growing conditions, style or wine to be produced, market forces - all play their part in how many grapes that will be harvested from each vineyard.

Due to differing viticultural practices and winemaking for different styles of wine, and diverse composition of different varietals, the amount of wine produced from a unit of grapes can vary greatly. It is difficult to make an exact conversion between these units. While yield can be seen as a quality factor in wine production, views differ on the importance of low yields to other aspects of vine health and canopy management. There is a consensus that if vines are cropped with a high number of grape bunches, a less complex wine can result because of slow, uneven, incomplete ripening, due to an unfavourable leaf surface to fruit ratio.

As the grape ripens, it draws on reserves from the leaves. The leaves collect sunlight and use its energy to produce carbohydrates - (i.e. photosynthesis). These are transferred into the grape during ripening, and result in an accumulation of sugars, flavour compounds and tannins. The less fruit the vine has per its leaf area, the more flavour, colour and tannin it can assemble during ripening.

Think of the vine leaf canopy as a solar panel, and each grape as a small light bulb that is connected to the panel. One canopy practice involves manipulating the position of the vine shoots to allow better interception of sunlight by the leaves. This is done by trellising the canopy in such a way that it is split it into various layers, by lifting the shoots up off the natural drooping position, into a more upright position using wires attached to the vine trellis. If done well, this can result in higher yields with no obvious reduction in quality.

One school of thought subscribed to in France, claims that great red wine is impossible to produce at yields exceeding 50 hl/ha. Another claims that a yield of 100 hl/ha is possible to combine with high quality, provided that careful irrigation *(which is allowed in New World wine regions), canopy management is used. In general, white grapes are seen as less sensitive to higher yields, whereas some varietals such as Pinot Noir, Sangiovese and Nebbiolo are particularly sensitive to over cropping.

In France and Italy, the maximum allowed yields are regulated by their wine laws and vary between appellations. Italian wines are labelled with a DOP or DOCG - the yields are controlled and limited by law, so you cannot call a wine Chianti Classico or Brunello di Montalcino if the yield is not below a set limit. Italy has long recognised that managing fruit yield is a quality boost to their wines, setting up appropriate regulations & labelling requirements to protect their wine's reputation.

Another factor is how ‘hard’ grapes are pressed; this will impact the final volume of wine yield. A winemaker can choose to use only the free-run juice (or first pressing) during crushing and maceration, reducing the yield volume by 30-40%. Yields can vary from commercial quantities of about 20-30 t/ha to super low levels of around 1-2 t/ha for example with old, dry grown bush vines. At 'average' volumes - 1 ton of grapes results in a little more than two barrels of wine. Each barrel contains about 225 litres or 300 bottles.

NZ example: Still Wine - on average approximately 1 ton of grapes = *750 litres of juice.

AOP Limit example: Champagne - approximately 1 ton of grapes = *510 litres of juice - *(tête de cuvée - first pressing).

What is an appropriate yield, depends on a number of factors, but also important is the style of wine being crafted, and how the grape varietal is grown. If a winemaker wants to make an affordable light-medium bodied wine, with a bright to moderate concentration of flavours and ideal for early drinking, then it makes no commercial sense to crop at the low levels. The reason why consumers have such a large choice of good value wines under NZ$20 is because many wine producers crop their vineyards at the medium to higher end of the yield scale for that varietal, wine style.

So if you see a bottle of wine over NZ$30 dollars, a good explanation will be lower yields, possibly only using the first pressings and this more complex, quality fruit can also respond well to the added costs and time in oak barrels etc. So grape vine cropping yields have a strong correlation to the final wine style crafted and therefore the price.